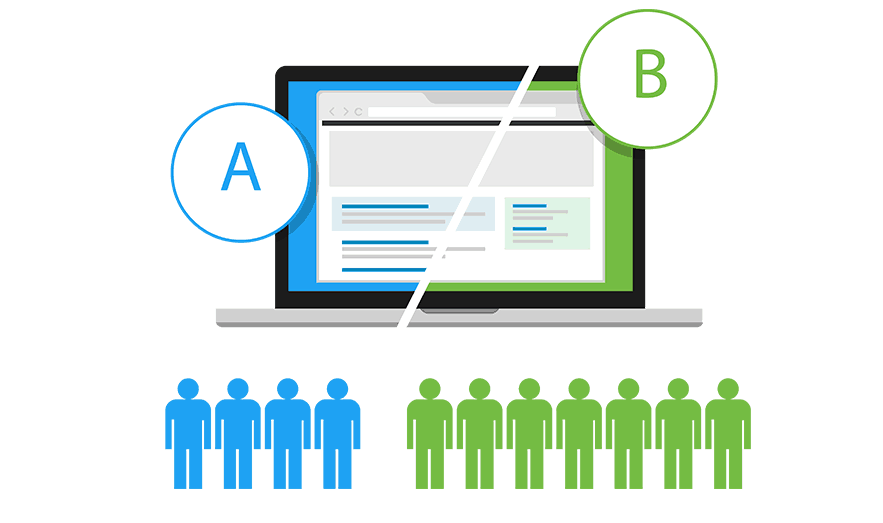

We do this because, with a large enough sample of the audience, we can ensure that except for the change that we have introduced in the product, all else is equal between the two groups of users that are split in half randomly.

And this can then lead us to conclude with a high degree of certainty that whatever effect we see in the group of users that were exposed to the change we released that is different from the other group, that difference is due to the change we have introduced.

Whether this difference turns out to be a success in inducing behaviours that we care about or is a failure, we can conclude that it is because of the change we introduced and then decide to act accordingly - release it to the other half as well if it is a success and roll the change back from the half that were exposed to it if it was a failure.

We do not release to all users, and then observe their behaviour and conclude whether it was a success or a failure because all else is no longer equal when comparing users from a different time period to the users that interacted with the product in the time period after the feature was released.

At the same time, we refrain from launching multiple new features in the A/B test because the difference we observe is then not attributable to any one feature that was released. All we can comment on is the combined effect of all the features that were released together. Even if such a release resulted in a successful A/B test, we wouldn't know the reason for the success.

In real life, however, we can't really run A/B tests on ourselves or on others. We only have one shot at writing an exam or giving an interview or playing a football match, and we can't split that exercise in half meaningfully enough to attribute why we do well or fail to do well in these activities.

A football manager that sets up his team in a certain formation and tactics with the hypothesis that this will result in a win, should he go on to win, can come away thinking that his tactics and formation worked, which it did in this case. But he cannot know how probable it was that he would be successful every time he uses it. So he goes on to use the tactics and formation until the day it doesn't work, and quite often, continues to use it for a while even after it stops working.

Yet, we look at successful people and try to emulate them all the time, as though what they did was the reason why they succeeded.

Just because one path lead one person (or a handful of people) to success, doesn't mean that the same path will lead others to success as well.

It should merely serve as inspiration, and not a map.

CONVERSATION